The greatest mass extinction event at the end-Permian of about 250 million years ago, often called the Great Dying, killed more than 80% of marine species and it took about 5 million years for the ecosystem to recover. The Great Dying and subsequent delayed biotic recovery may have linked to the dynamic mixing of deep sulfide-rich waters and shallow oxic waters, according to a new study led by Prof. SHEN Yanan, from the University of Science and Technology of China.

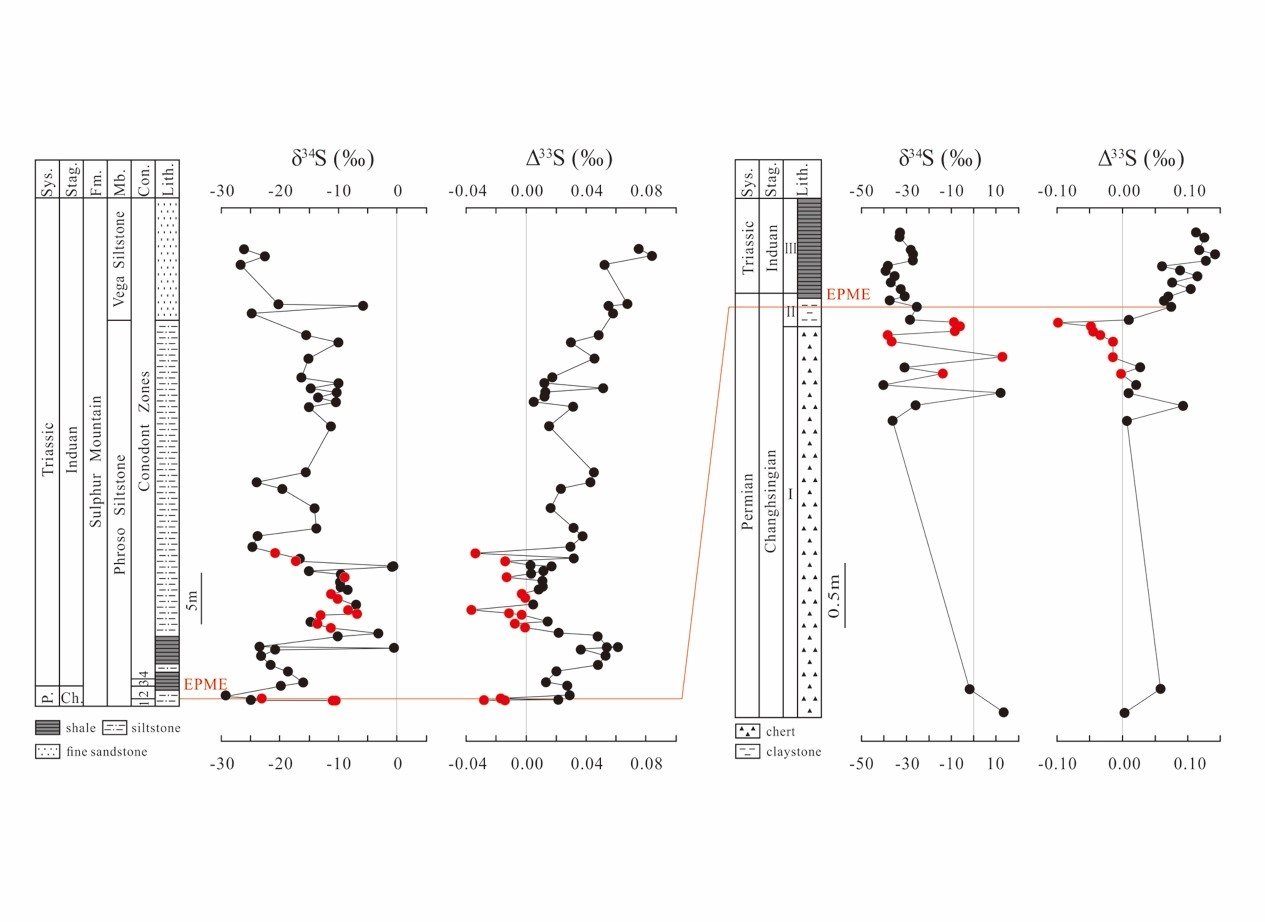

Researchers analyzed multiple S-isotopic compositions of pyrite on the rocks samples which were deposited in the Panthalassic Ocean now preserved in outcrops of Canada and Japan (Fig. 1). Due to tectonic subduction, the deep sea sediments have almost completely lost, with only preserved in Canada, Japan, and New Zealand. The rarely-preserved sediments in Canada and Japan offer new insights into global ocean chemistry changes during Permian-Triassic because the Panthalassic Ocean occupied about 85-90% of the contemporaneous global ocean area.

Fig. 1. Multiple S-isotopic data for the Opal Creek (Left) and Gujo-Hachiman (Right) sections.(By SHEN Yanan)

ZHANG and his colleagues discovered sulfur isotopic anomaly before, during, and after the Great Dying. The S-isotopic anomaly before the extinction event suggest sulfide-rich waters in the deep Panthalassic Ocean but oxic shallow waters, in contrast to the modern oceans. The precise coincidence between the extinction and sulfur isotopic anomaly reflect mixing of toxic sulfide-rich waters from the deep with oxic waters in the shallow, according to the authors. Sulfide is toxic and it is lethal to humans even with low concentration of a few hundred parts per million. Therefore, mixing of sulfide-rich waters and oxic waters would kill marine animals in the Permian-Triassic oceans. The similar sulfur isotopic anomaly also presented in the Early Triassic sediments suggest that oscillation between sulfidic and oxic conditions may have contributed to the protracted recovery of marine ecosystem.

The study may have present-day relevance because many coastal areas such as the Namibian coastal waters, Gulf of Mexico, California, western India are enriched in sulfide due to human perturbation and global warming. As such, the study may serve as a good example of “the past is the key to the present”. The paper by ZHANG et al. was recently published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The link of the paper: http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2017/02/03/1610931114.figures-only

Contact:

Prof. SHEN Yanan

E-mail: yashen@ustcnet.