A research group led by SUN Ruoyu from University of Science and Technology of China, suggests that corals in the South China Sea may have taken up the metal, keeping a record of wars locked in their skeletons. The finding provides a look at how humans have been polluting the ocean throughout history, and may help us understand how the metal travels in our atmosphere today.

Scleractinian corals build skeletons with aragonite, a calcium carbonate mineral, separated from ambient seawater. Some particular type of metal like Hg can take the place of calcium and be incorporated into the skeletons of corals. Thus, annually banded coral skeletons can be a unique archive to track the variations of elements in the ocean. However, Hg measurement in coral skeletons is a great challenge as the extreme low concentrations.

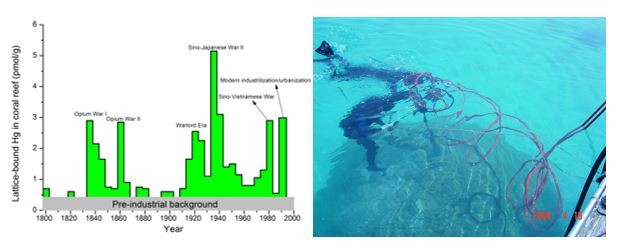

SUN's group extracted a 200-year-old core from a Porites lutea coral in the northern South China Sea and developed a combustion-trapping method for highly accurate total Hg measurements. While the levels of mercury were low and relatively constant in the oldest part of the core between 1800 and 1830, The amount of mercury spiked repeatedly with enrichment factors of 4-12 over the coral’s next 170 years of life. Five spikes line up precisely with a number of violent conflicts in dates and scales including period 1833−1847 (the First Opium War), 1858−1862 (the Second Opium War), 1918−1927 (the Chinese warlord era), 1933−1942 (World War II), 1978−1982 (the Sino-Vietnamese War). The other spike between 1988 to 1992 is related to the industrialization and urbanization of Chinese coastal cities.

"We never expected [mercury] would come from the wars,” SUN says—but there’s a good reason why it would. The metal is used in the production of weapons and explosives, and their detonation could also release mercury into the air. When the elemental form of mercury in the atmosphere encounters reactive chemicals like bromine ejected from the ocean via sea spray, it forms what researchers call “reactive gaseous mercury” molecules. These then settle into the ocean, after which corals can take up the dissolved mercury into their skeletons.

Once considered a more long-lived chemical that travels vast distances as it drifts through the atmosphere for a year or more, the impacts of mercury are increasingly being thought of as more local. "We’re revising that down to the order of months." Hannah Horowitz, an atmospheric chemist at Harvard University says. The Science News also reported the research with “World War II, Opium Wars recorded in ocean’s corals” and presented exclusive video interview.

This work published in May in Environmental Science & Technology entitled "Two Centuries of Coral Skeletons from the Northern South China Sea Record Mercury Emissions from Modern Chinese Wars".

Link: http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.5b05965

The research was supported by the National Key Basic Research Program of China, the Strategic Priority Research Program, CAS, National Science Foundation of China, State Key Laboratory of Loess and Quaternary Geology, Institute of Earth Environment, CAS, and Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation.

(HUANG Xingxing, USTC News Center)